Sue Edwards, senior lecturer in career guidance at the University of Huddersfield, introduces a new Textures of Groupwork model to support the development of training programmes for careers professionals

The use of graduate outcomes data as a measure of success of a higher education institution (HEI) has been a key driver for the current 'employability' agenda within higher education and in particular, the careers services within them.

This focus on increasing the number of graduates progressing into highly skilled graduate-level employment or further study, alongside growing student numbers and extended access to lifelong careers services within a context of limited budgets, means HE careers services have been prompted to shift their attention to supporting undergraduates to develop their employability and thus increase students' chances of securing graduate-level employment.

With an estimated ratio of careers staff to student standing at 1:9951, many HEIs have turned to a 'one-to-many' approach to meet the support needs of their students, often in addition to, or in some cases in place of, a one-to-one service, which has often been considered the traditional bedrock of a HE careers service.2,3 The interest in one-to many approaches is also gaining attention from budget holders in other sectors of the profession, including schools and colleges, in a bid to find more cost-effective ways to meet the career development needs of young people.

Within this shift to a one-to-many approach, Group Career Guidance (GCG) has gained momentum as an innovative approach to supporting students' career development. However, a lack of UK-based literature, specifically addressing the practice of group career guidance, has led to confusion and ambiguity about what it is, how it differs from other careers focused groupwork and how it can be implemented,4,5 and perhaps even more importantly, whether it is actually a cost-effective alternative.

This article introduces the Textures of Groupwork model and aims to define the unique characteristics of various types of career development and employability focused groupwork with specific emphasis on GCG in order to inform the development of training programmes for career development practitioners (CDPs).

Why bother identifying distinctions?

Discussions with practitioners who have joined a community of practice focused on GCG, highlight that there are different interpretations of what GCG is, and how it is different to other forms of career focused groupwork. Mcloughlin's6 research with CDPs identifies the role 'clarity of language and meaning' has when implementing new and innovative forms of practice and demonstrates how practitioner uncertainty about what GCG is fuels the resistance to using it.

Much like one-to-one work, where it is recognised that information, advice and guidance (IAG) each have their own benefits and limitations, it is important for the practitioner to recognise the limitations of the groupwork approach that they utilise. GCG is often perceived to be a cost-effective approach to providing career support.7 However, this perception is based on a limited understanding of the efficacy of GCG within UK educational settings.

Evidence from the Career Registration project shows that at any given point within the undergraduate journey, including final year, the largest group of students are in the 'decide' phase of their career readiness,8,9 which reinforces the importance of the careers services utilising groupwork in a way that supports the guidance needs of students rather than their information and advice needs.

Potential benefits of group career guidance

Many helping professions, including counselling and coaching, have embraced group-based practice. Whitaker10 lists a range of potential benefits of groupwork within other helping professions, including the value of recognising that others are experiencing similar challenges thereby reducing a sense of inadequacy or feeling isolated, a sense of catharsis as people get to tell their story and have it validated and recognised by others, seeing new possibilities and challenging previously held assumptions.

The introduction of the group to the process of guidance provides an opportunity to broaden the perspectives and understanding of the individual in a way that isn't easily replicated in one-to-one guidance.11,12 This impact of groupwork is further explored by Meldrum13,14 who argues that career focused groupwork can also be a catalyst for emancipatory change. Di Fabio & Maree15 applied the Life Design Counselling approach16 to group work situations and noted that the additional element of being in a participatory group supported the reflective process to take place.

Their work suggests that group career guidance has the potential to be more beneficial for participants in comparison to one-to-one guidance due to individuals having the opportunity to share their stories/ ideas, listen to others, reflect on and comment on others or, as Di Fabio and Maree put it, 'The role and power of the audience stemmed predominantly from the fact that each participant was given the rare opportunity to be both actor and member of the audience during the life design intervention 'play'.17 However, it is also worth noting that the group aspect is not suitable for all individuals, particularly those that are uncomfortable in interactive group settings.18

Introducing the Career Groupwork continuum model

I have developed the model in response to the lack of clarity about what constitutes GCG and in trying to answer the question: 'How is GCG different to other forms of groupwork that career development practitioner might use?' It attempts to acknowledge the differences and overlaps within different types of groupwork, as well as the different outcomes that can be achieved through different groupwork approaches. The model draws on over 25 years of facilitating learning in groups, in both traditional education settings and within the community. It has been shared with CDPs interested in GCG through a LinkedIn community of practice group and with colleagues in the CIAG Policy and Professional Practice Team at Skills Development Scotland.

Each time the model has been shared it has prompted reflective discussion on groupwork approaches and feedback has thus far been that the model is useful when considering what can be achieved through the use of groups in career development and employability work. The intention of the model is to support a common understanding of different types of groupwork, what each consists of and what can be achieved by using that approach, so that practitioners can be purposeful in their choice of groupwork approach.

A key aspect of the continuum model is that it is not suggesting that any one type of groupwork is superior to others - they all have their place in the practitioner tool kit. I use the phrase 'Textures of Groupwork' to reflect that different type of groupwork have a different 'feel' both for the practitioner and for the group participants.

Identifying fundamental differences

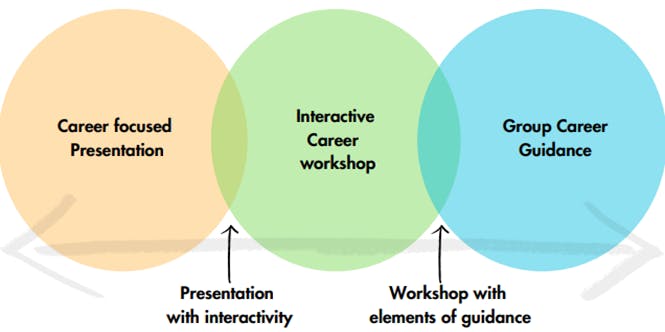

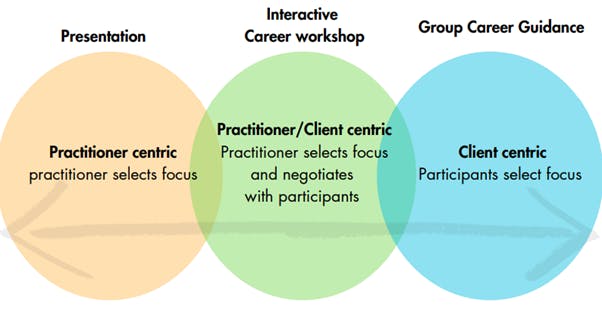

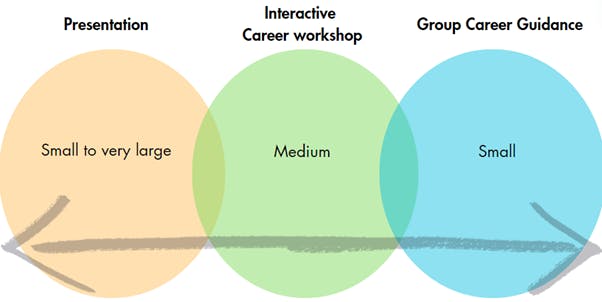

The first aspect of the continuum acknowledges the overlap between different forms of group work. Presentations sit at one end of the continuum and group career guidance at the other, with interactive career workshops in the middle. The continuum recognises that presentations can have elements of interactivity, but perhaps not as much interactivity as can be achieved in a smaller workshop situation. Similarly, there is scope for an interactive workshop to have elements of career guidance incorporated into them. The defining characteristics for each type of groupwork are examined further within the model.

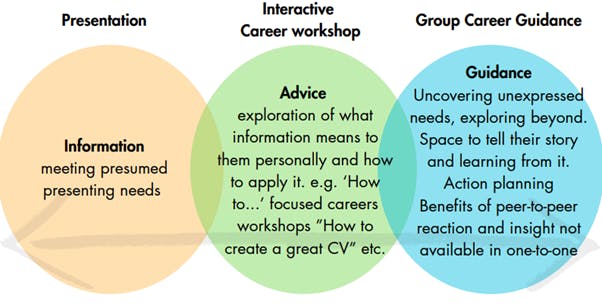

Mirroring the use of IAG in career conversations

The model considers how groupwork can mirror the way CDPs use IAG approaches in one-to-one conversations. Presentations often meet the presenting needs of the participants that have been gathered prior to the session. A workshop often includes an opportunity for participants to explore the information in more detail and consider how they might apply it to their own circumstances, in a similar way that advice is used in one-to-one interactions. GCG provides an opportunity for participants to tell their story, with the practitioner uncovering unexpressed needs that may not have the opportunity to be aired in other group formats.

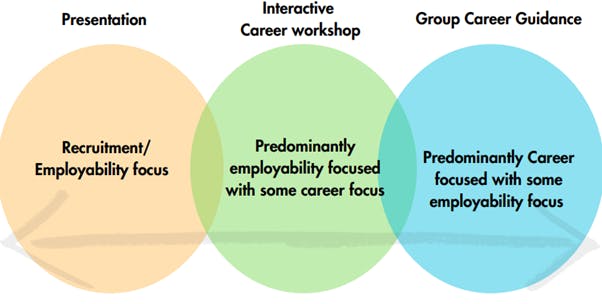

Career and employability

Bob Gilworth's statement that 'all employability and no career is like the luggage without the map'19 is particularly relevant when we consider the purpose of groupwork. Daubney20 explains how maps are used to understand where one currently is on their journey, to discover places they can go, decide what is of interest, how the journey might consist of smaller journeys, learn possible routes to reach the next destination and decide on the next leg of the journey. It is personal and bespoke. 'Employability' is represented by the luggage, those things that are needed to make that journey, recognising that different journeys need different things (this could be specific skills, information, and that different things can be picked up along the way of the journey). It highlights that there are things in the luggage that are unique to the individual, but also that there are also many similar things to other people's luggage. It is more generic.

Through the continuum model I propose that different types of groupwork support different aspects of 'career and employability'. Daubney21 argues that while employability can be delivered in a one-to-many capacity, due to its personal nature 'careers' activity cannot be effectively delivered in this way. This sentiment is echoed by many careers practitioners with Meldrum22 noting that within the careers sector, one-to-one guidance has often been regarded as the most effective way to 'facilitate growth at an individual level'.

The continuum highlights the limitations of the different types of groupwork, and while we might conclude that typical career education activities that include presentations and workshop style groupwork are not conducive to 'career' focused outcomes, I propose that GCG has the potential to 'facilitate growth at an individual level' in a way that other groupwork activity is not able to due to its employability focus. This is particularly relevant when considering where the majority of undergraduate students are in their journey. If careers services focus their one-to-many interventions on the 'Compete' stage of career readiness, e.g. how to create a great CV, prepare for interviews, etc, then there is the potential that the needs of students in the Decide phase are not being met through the typical range of one-to-many activities as seen in HE Careers Service programmes.

Differences in focus, ownership and outcomes

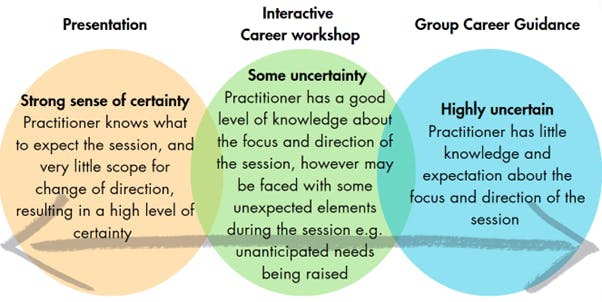

Practitioner certainty

CDPs need to be comfortable with uncertainty in their one-to-one practice in order to be open to hearing the client's story and to ensure they are not being directive. CDPs empower clients to take ownership for the content of the discussion and this is mirrored in the continuum.

Focus and ownership

Ownership and control

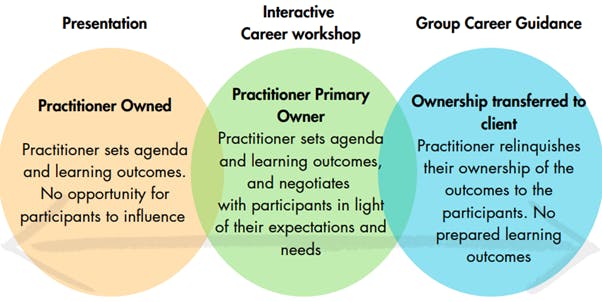

Similarly, issues related to differences in the ownership of the group can be expressed through the continuum.

The continuum model proposed that another defining feature of GCG relates to who is setting the agenda for the interaction. Within a one-to-one career guidance interaction, individuals are empowered to identify the needs that are of most importance and urgency to them. The continuum acknowledges that this level of ownership shifts depending on the type of groupwork, with the practitioner maintaining ownership of the group in a presentation style groupwork setting and the practitioner relinquishing control in GCG in a similar way to one-to-one interactions.

However, this does not mean that the CPD just sits back and lets the group do their own thing. The role of the practitioner is to create a psychologically safe space and maintain the structure of the group conversation and support the participants to manage the dynamics within the group. Just as practitioners build a working alliance and enter into a contracting phase to agree the purpose of the conversation with their clients in a one-to-one career guidance interaction, within GCG CDPs will facilitate the group to identify their needs, build a working alliance and set the goals (outcomes) for the session. This is in contrast to other forms of groupwork where learning outcomes are deemed essential to support the learning process.

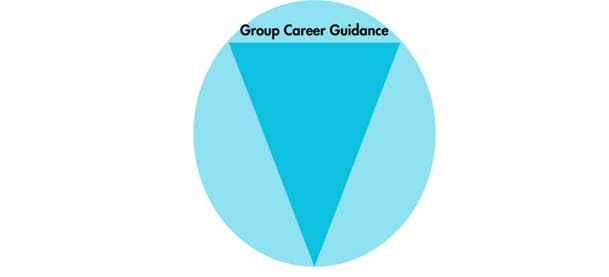

Practitioner input

The diagram above represents the shift in the level of practitioner input within GCG.The practitioner plays a significant part in establishing the psychological safety of the group, establishing needs and facilitating these processes. The practitioner gradually relinquishes control, empowering the group to take ownership of key elements such as how the group will work together, what the purpose of the session will be. which also echoes theory related to small group development such as Tuckman and Johnson & Johnson.23,24

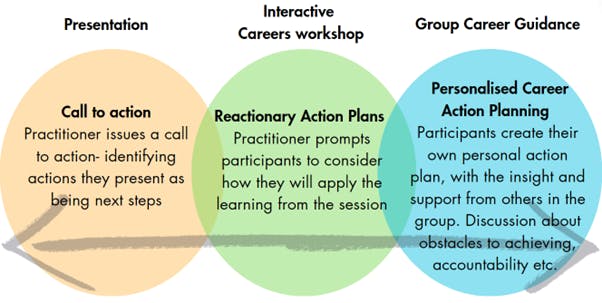

Action planning

Action planning is considered an essential part of the one-to-one career guidance interaction, the continuum considers the differences that might occur within different forms of groupwork.

Group size

In order to allow all group participants to have their needs met, to have space to tell their story, engage in personal exploration and action planning, the size of the group is an important consideration.

The CDI positional paper relating to GCG suggests that GCG should take place in groups of not more than four, whereas Pyle & Hayden25 suggest that group size can be between four participants and eight. This seems to be an aspect that warrants deeper investigation and understanding.

Moving forward

As the continuum model evolves there are other practical aspects to explore to support CDPs to develop a common understanding of what GCG is and the range of skills and techniques that CDPs would need to master in order to effectively facilitate GCG.

Other elements that are being included in the research to consider how they fit into the continuum model include:

- Approaches to using information and resources

- Number of/length of sessions (i.e. can a one-off one-hour session 'facilitate growth at an individual level' for all participants? - linking to questions related to cost-effectiveness)

- Language

- Prevalence of Rogers' Core Conditions26

- Levels of reflectivity and reflexivity

- Influence of the client

- Agency and autonomy

- Belonging & commitment

The continuum model is a work in progress: the next stages of my PhD research focus on refining this model using a co-creation methodology to develop a robust model that can support CDPs to better understand the benefits and limitations of different groupwork methods, and testing its validity by engaging with CDPs who deliver careers work in group settings.

Findings from the research project are likely to be particularly relevant for heads of careers services, who make decisions about what their service offer includes. A deepened understanding of the potential of group career guidance to support undergraduates in their career readiness can lead to better informed decisions about whether to include group career guidance in their service offer or not.

Findings will also inform future training and ongoing professional development of CDPs through the identification of the skills, processes and the underpinning theory and pedagogy of effective group guidance.

Notes

- The resourcing of HE careers services through the pandemic and beyond, AGCAS, 2021.

- Thomsen, R. (2012). Guidance in communities - a way forward? Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 28(1), 39-44.

- Yates, J. & Hirsh, W. (2022). One-to-one career conversations in UK higher education: practical approaches and professional challenges, Journal of Further and Higher Education.

- Meldrum, S. (2017). Group guidance - is it time to flock together? Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 38(1), pp.36-43.

- McLoughlin, H. (2022). How can we do this? an investigation of power constraints and other barriers to career development practitioners' innovation in higher education. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 49(1), 18-26.

- Ibid.

- Meldrum, S. (2017).

- Cobb, F. (2019) 'There's no going back': The transformation of HE careers services using big data. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 18– 25.

- Gilworth, R. (2022). Starting Points and Journeys: Employability Strategy in a Data-Rich Environment. In T. Broadley, Y. Cai, M. Firth, E. Hunt, & J. Neugebauer (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Graduate Employability (1st ed., pp. 452-473). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Whitaker, D. S. (2001;). Using groups to help people (2nd;2; ed.). Brunner-Routledge.

- Pyle, K.R. & Hayden, S.C.W. (2015) Group Career Counseling: Practices and Principles. Second Edition. National Career Development Association.

- Higgins, R., & Westergaard, J. (2001). role of group work in career education and guidance programmes. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 2(1), 14-17.

- Meldrum, S. (2021). Group career coaching - A critical pedagogical approach. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 46(2), 214-225.

- Meldrum, S. (2022). Agents for change: Reimagining emancipatory career guidance practices in Scotland. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 49(1), 41-49.

- Di Fabio, A., & Maree, J. G. (2012). Group-based life design counseling in an Italian context. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 100-107.

- Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J. -P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., et al. (2009). Life Designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75, 239–250.

- Di Fabio, A., & Maree, J. G. (2012).

- Pyle, K.R. & Hayden, S.C.W. (2015).

- Quoted in Boundaryless Careers? A Space Oddity. Third Space Perspectives - Exploring Integrated Practice, Watt, S, 2024.

- Daubney, K. (2021). Careers education to demystify employability: A guide for professionals in schools and colleges (First ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Ibid.

- Meldrum, S. (2021).

- Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100.

- Johnson, D. H., & Johnson, F. P. (2013). Joining Together Group Theory and Group Skills (International ed of 11th revised ed). Pearson Education Limited.

- Pyle, K.R. & Hayden, S.C.W. (2015).

- Rogers, C. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 21, 95-103.

Other references

- Blum, L. P. (1971). Vocational Guidance Through Groups. In Hansen, J. C., Cramer, S. H., Group guidance and counseling in the schools: Selected readings. essay, Appleton Century Crofts.

- CDI, (No Date) Positional Paper Personal Guidance and Group Careers Guidance. Available at https://www.thecdi.net/write/Personal_Guidance_and_Group_Careers_Guidance_-_CDI_recommendation.pdf[Accessed 13th August 2023].

Was this page useful?

Thank you for your feedback