Ahead of the publication of What do graduates do? 2021/22 in January, Charlie Ball provides an overview of the labour market faced by those who graduated from their first degree in 2018/19 and took part in the most recent Graduate Outcomes survey

2020 was a year dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The word 'unprecedented' is tossed around a little too lightly at times - most economic events have happened in broadly similar ways in the past - but a pandemic on this scale had not been seen for a century.

The effect on the world economy in general, and on the labour market in particular, was transformative. In the UK, lockdowns were imposed and a massive set of furlough schemes was put into place to allow workers whose employment was suspended to remain employed and paid while businesses was shuttered. Overall, 26% of the UK workforce was furloughed at some point.1

However, the very large majority (92%) of people who were furloughed returned to work. And graduates were much the least likely group of workers to have been on furlough.2 But younger workers and new entrants to the labour market were hit particularly hard as vacancies collapsed, internships, work placements and apprenticeships were cancelled and employers ceased recruiting.

At its worst, in May 2020, online vacancies in the UK were at 37.9% of their pre-pandemic levels just three months previously.3 And the large majority of this data was collected during the pandemic. It is against this extraordinary backdrop that we examine the data for graduates for 2018/19 15 months after graduation for this year's What do graduates do?.4

The crucial matter to consider is that this cohort of graduates did not graduate in the pandemic. The data for that cohort will appear in the next edition of this publication. This data covers graduates who left university the previous summer and so, in most cases, had been in the labour market a few months when COVID-19 hit the UK.

The data

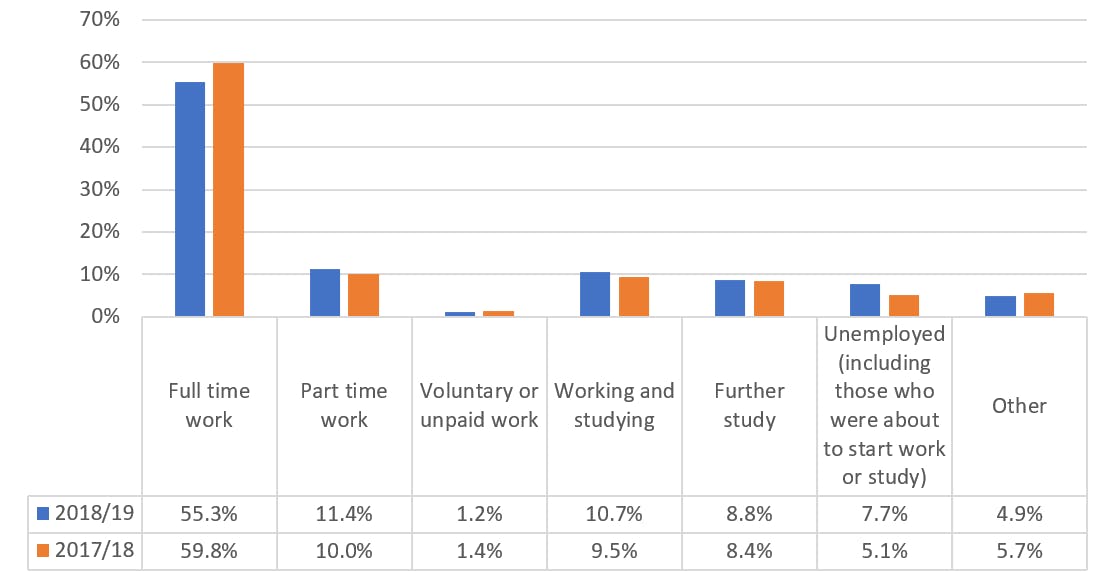

As Figure 1 shows, there was perhaps less of a difference between the two cohorts than might be expected. The proportion of graduates from the 2018/19 cohort who were employed after 15 months was slightly lower than for the previous year, but the difference was small. In fact, because the 2018/19 cohort was a little larger, more graduates from that year were working 15 months after graduation - in other words during the pandemic.

Meanwhile 4.3% of the cohort were self-employed, with education, graphic design, photography and AV, artists and arts officers, producers and directors the most common occupations, despite the arts sector being one of the very worst hit by the pandemic.

Unemployment was unsurprisingly up, but an increase in base unemployment was not the only factor. There was also an increase in the proportion of graduates unemployed at the time of the survey but who already had something lined up to start within a month - even though the jobs market was in an exceptionally difficult state. This lines up with all the other observations from other data sources: a degree was one of the best insulations against sustained career disruption during COVID-19 that an individual could possess.

Also down was the 'Other' category. Traditionally the majority of this group are graduates who are travelling, but for obvious reasons these numbers were substantially down on the previous year. Overall 72.4% of those employed were in professional level employment, a very modest fall from the previous year. But the detailed figures tell an interesting story. Much the largest rises in employment among non-graduate jobs were in key worker roles in social care - particularly for the elderly and disabled - and in supermarket retail. It would be a very curious argument to suggest that graduates working in care of the elderly in 2020 were not performing worthwhile activity and this calls into question the 'graduate/non-graduate job' divide.

The most common roles for graduates from 2018/19 remain familiar – nursing was comfortably the most common job and, not surprisingly, saw a strong rise in numbers. IT took second spot, also rising (marginally) year on year, primary school teaching was third, despite a fall in numbers, and medicine, another riser, took fifth. Marketing saw the single largest fall of any profession, down 15.5% in numbers (with the advertising industry a very significant component of that fall), but was still the fourth largest job by numbers.

A degree was one of the best insulations against sustained career disruption during COVID-19.

The future

The graduate jobs market held up despite the pandemic. Annual Population Survey data from the Office of National Statistics shows that at the end of 2020, there were 16,171,100 people working in professional-level employment in the UK, up substantially on 2019 despite the pandemic. If COVID-19 does not stop the expansion of professional-level employment in the UK, it is difficult to see what will.

One issue many are concerned about is AI, and in October the government's Business, Education, Innovation and Skills (BEIS) department published a mammoth analysis by PwC of the likely effect of AI on the labour market.5 Around 7% of existing UK jobs could face a high (over 70%) probability of automation over the next five years, rising to around 18% after ten years and just under 30% after 20 years. AI will also create many jobs through the boost it gives to productivity and economic growth.

While some of these extra jobs will be in areas linked directly to AI and related technologies (e.g. data scientists, robotic engineers or people involved in the design and manufacture of sensors for driverless vehicles and drones), most of the additional employment will not be in high tech areas. Instead, these additional jobs created will mostly be in providing relatively hard-to-automate services (e.g. health and personal care) that are in greater demand due to the additional real incomes and spending arising from higher productivity generated by AI.

Overall, demand for graduates is expected to increase, with about a 10% increase in expected roles due to AI. Broadly, demand for post A-level qualifications is expected to increase while demand for qualifications at A-level or below is expected to fall. It looks as if a degree is likely to hold its value in times of disruption for a little while yet.

Notes

- An overview of workers who were furloughed in the UK, Office of National Statistics, 2021.

- The IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities, Institute of Fiscal Studies, 2021.

- Data from the ONS.

- Graduate Outcomes 2018/19, HESA, 2021.

- The impact of AI on jobs, BEIS, 2021.

Was this page useful?

Thank you for your feedback