Charlie Ball uses Graduate Outcomes data to consider the migration patterns of university leavers and how much has changed - or not changed - in the last decade and a half

This article examines our classification of graduate populations based on their domicile, location of institution and location of employments using Graduate Outcomes data for graduates from 2017/18 15 months after graduation, discusses the findings, and considers what insights they provide for a post-COVID graduate employment market.

In the Summer 2005 edition of Prospects' labour market publication, Graduate Market Trends, we introduced a new classification of graduate populations based on migration, using data for graduates from 2003 six months after graduation. Graduate Market Trends has since been replaced by Prospects Luminate, but the original article can be read here.

- Regional loyals - these are graduates who are domiciled in a region, went to study in the region, and remained to work in that region. They make up the largest group of graduate employees from 2003 in most regions. They often take up positions in health or social care.

- Regional returners - these are graduates domiciled in a region, who go elsewhere to study, and then return to their home region to work. In many regions, these make up the next largest group of graduates.

- Regional stayers - these are graduates who travel away from their home region to study, and then stay in that study region to work. They are quite likely to enter the health sector to work.

- Regional incomers - these are graduates who go to work in a region in which they neither studied nor were domiciled. They often come to a region for jobs which may be higher paid, in management, engineering, or science.

In the 16 years since this article was published, we have used these categories to examine graduating cohorts and the classification has become used more widely. But this is the first time we have used Graduate Outcomes, taken after 15 months.

Regional employment categories for graduates from 2017/18, 15 months after graduation, Loyals,42.1 Stayers,11.5 Returners,24.2 Incomers,22.1

This data is not substantially different to the pattern we saw for graduates from 2003 six months after graduation. Despite nearly two decades and one major recession, graduates work-seeking behaviour, at least in geographic terms, remained reasonably constant.

By far the most important category in this analysis are the Loyals. Over 40% of all first-degree graduates from university have not moved away from their home region for study or work 15 months after graduation. This is a long-standing and resilient pattern and ought to be viewed as the commonest and most typical behaviour for graduates. Loyals are more likely to be women, and are more likely to work in the public sector, although they are still very likely to be in graduate-level employment.

The next largest group are Returners, who move away from home for university, and return home to work on graduation. They are much the most likely to struggle in the jobs market - many have returned home as they have not secured employment elsewhere. This can be an issue, especially when inexperienced graduate return home to weak labour markets and away from the support they had available at their institutions. That said, a comfortable majority are in graduate level employment. They are actually quite likely to be from affluent backgrounds.

Incomers are the next largest group. This group is slightly larger than after six months (when they typically made up around 20% of the cohort). These are the group who demonstrate what is often viewed as 'typical' graduate job seeking behaviour - they go away from home from university and then move again, usually to a large city, on graduation. Indeed nearly half of Incomers work in London and they are much the largest group of graduates employed in London. Nevertheless, it is a minority of graduates who go to work in labour markets to which they do not already have an existing connection, and basing provision and policy on the assumption that this behaviour is common or typical, or that graduates who do not undertake this activity are in some way 'lacking ambition’ or are of lower quality than those who do is an error. Nevertheless, Incomers tend to be clustered in better paid jobs (note, it does not automatically follow that they demonstrate the highest satisfaction with their careers or university experience) and are very likely to be in professional level employment. They also tend to be from the most affluent backgrounds.

Finally we have the Stayers. This is the smallest group and consists of graduates who left home to go to university and who stayed close to their institution to work. This group is the second most likely to be in professional level employment, and are actually quite likely to be from backgrounds of low HE participation.

Regional data

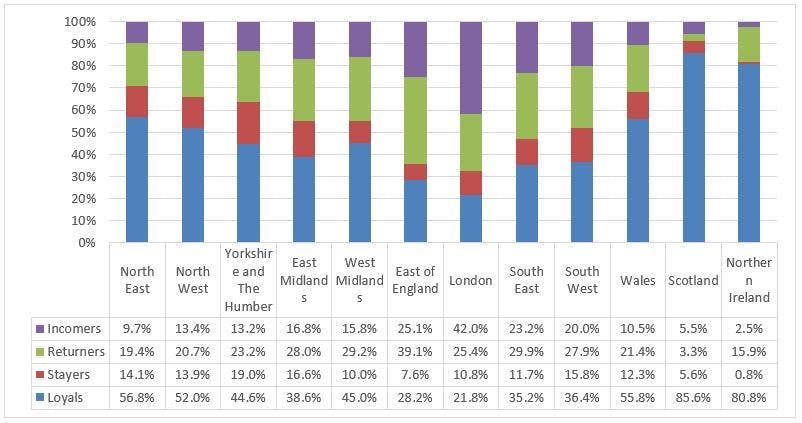

A national-level analysis only supplies a limited picture of the important regional nuances of labour market supply and the behaviour of graduates in the way they move for work. Chart 2 looks at each region.

Chart 2: Regional employment categories for graduates from 2017/18 15 months after graduation by region

The three devolved nations are included for completeness but to do the complexities of local labour markets justice we need to break internal geographies down. We have done this in conjunction with AGCAS for the Scottish labour market using Destination of Leavers of Higher Education data after six months and future efforts will look at these important labour markets in more detail.

In England, the majority of graduates in the North East and North West are Loyals, who go to local institutions and work locally. Any examination of the 'levelling up' agenda in the North must take this tendency into consideration; local anchor institutions will be absolutely central to this effort.

London is, unsurprisingly, another anomaly, and here the patterns of 'Loyals' and 'Incomers' are reversed, with Incomers making up almost half the cohort of new graduate employees due to the capitals demand for skilled employees. The East of England is another unusual region in that it has an unusually high proportion of Returners - this is allied, unfortunately, to parts of this region having weak graduate labour markets (although Cambridge's very strong jobs market is also located here).

Elsewhere, the other regions show a fairly typical pattern, with Loyals the largest group, followed by Returners, Incomers and Stayers being the smallest group.

Overall, this means that from this cohort around 66% of graduates were working in the region they were domiciled in before university 15 months after graduation, and 54% were working in the region where they went to university. Most graduate work in a region to which they had a connection before working, this has been the case for many years, and it is important to consider this when examining graduate labour market supply and demand.

The link between location of work and location of employers may start to erode, with important implications for the labour market and economy.

Post COVID

These patterns are long standing and have not hitherto changed much in the nearly two decades since we began looking at them in earnest. COVID-19 has, however, been highly disruptive. By the end of May 2021, approximately 29% of the UK workforce was working remotely, with a large majority of workers in the highly graduate IT and professional services industries working solely from home. Our larger urban labour markets have been seen particular economic impact as professional workers, normally graduates, have worked at home and services and retail have been hit accordingly.

A consensus is starting to emerge that many professional roles - including many for new graduates - are likely to transition to a hybrid model, split between home and office. This means that the link between location of work and location of employers may start to erode, with important implications for the labour market and economy. A graduate wanting to work for a London firm may no longer need to move to London, but can stay at home and visit the office on a less frequent basis, but with their home region retaining their skills and spending power. The other side of the coin is that businesses in unpopular, expensive or remote labour markets can now recruit more widely. It is also likely to become necessary to update this classification to take into account that people may live and work in very different places. It could well be that post-COVID these figures will start to look different.

However, many graduates will still be in the workplace most of the time, and thus will need to live within the travel-to-work area of their employer. This analysis is a timely reminder that most of the time, most graduates will live and work in regions that they already have a connection to, that graduates are perhaps not as mobile as is sometimes assumed and that employers looking to recruit need to be mindful that they are likely to attract applicants who have an existing connection to the location of the business.

Was this page useful?

Thank you for your feedback